The International Society of Radiology

by Otha W. Linton, MSJ

Former Executive Director of the International Society of Radiology

The International Society of Radiology was born in 1925, weaned in 1953 and given legal being in 1995. For 80 years, it has ebbed and flowed, sponsoring world meetings of radiologists, seeking a broader political and educational role and trying hard to do well while doing good.

The first medical x-ray society of record was founded in Britain in 1897. Professor Roentgen was invited to be an honorary member and declined. By 1897, he had completed his seminal work with x-rays and was resolved to go on to other physics challenges.

In the first weeks after Roentgen’s publication of his remarkable three articles B all he wrote B hundreds of physicists in the developed world learned what he had done and repeated his experiment. In the North American scientific literature alone, more than 1,000 articles appeared during 1896. Improvements in x-ray generating equipment, in tubes, in film emulsions and in understanding of this phenomenon of ionizing radiation tumbled into being. Some early investigators and physicians using x-rays were heedless of the threat to their own health from chronic exposures to unshielded x-ray tubes. The crude, low-energy tubes may have been a bizarre blessing. Higher energies would have caused widespread severe damage and public outcry might have forced abandonment of x-ray applications in medicine and science.

In those early years, doctors and scientists interested in x-rays made pilgrimages to the great physics centers in Germany, Austria and England, as well as to France to learn about the new natural radiations discovered by Henri Becquerel and developed by Pierre and Marie Curie. The havoc and destruction of World War I shattered Germany and Austria and forced scholarship to seek other venues.

So it may have been reasonable that the initiative for a world congress on radiation science and medical radiology came from Britain. There was no international organization to sponsor such a meeting. The founders decided to do it, made the arrangements and wrote to friends and to leaders of other national societies to invite attendance.

In the name of scholarly integrity, it is necessary to report that no official records exist from that first congress. There are contemporary accounts from which much information can be drawn. Whatever records were retained and passed along to organizers of the next congress were sent from Chicago after the fifth congress in 1937 to be used by German sponsors of the proposed 1941 congress in Hamburg. That congress was a victim of World War II. The records of international radiology were lost in the destruction of much of Germany by repeated bombing raids.

In 1925, attendance at a meeting in a foreign country was a major undertaking, requiring a month, perhaps two, for travel and visiting in addition to the actual week of the congress. For a radiologist from the western part of North America, the trip began with a three-day train ride, followed by a week transit of the Atlantic Ocean by ship, another train ride to the meeting city and, after such travel as could be crowded into available time, the route was reversed. For a physician from Japan or Australia or South Africa, the trip was even longer. The travelers were accompanied by trunks with heavy glass slides for speakers, with formal clothes for the dinners and if ladies were along, clothing suitable for two months in varied climates.

The London meeting was pronounced a success. Before its completion, arrangements were announced for a second congress three years later in Stockholm.

A major concern for most of those attending that London conference was the absence after 30 years of accurate and reliable ways to measure x-ray exposures. In particular, physicists who were part of the assembly urged a departure from the biological observations which physicians used in favor of more quantifiable physical phenomena which could be defined and replicated. The commonest way for early x-ray users to quantify patient exposures was the so-called “erythema dose” or skin reddening.

Committees in Britain, Norway, Germany and the United States had all made beginnings at defining x-ray doses and devising measurements. After discussions in London, those assembled decided that international efforts were indicated. Participating societies were requested to come to Stockholm in 1928 with possible approaches and schemes. Out of the Stockholm congress came creation of the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements and the International Commission on Radiological Protection. The series of reports produced by the two commissions created the system of measurements in worldwide use until the change to units in the 1960s.

The International Society of Radiology did not arise from these early congresses. A national society, having accepted the burden of organizing a congress, undertook the effort at its own risk, as national sponsors still do. There were no guidelines, no continuing medical education requirements, not even a general agreement as to what languages would be used. Indeed, after accepting the burden of sponsoring a congress, the organizing society’s second critical task was recruiting a successor.

If the Stockholm meeting was characterized by improvements in radiation science, the 1931 congress in Paris was graced by the presence of Madame Marie Curie, the discoverer and synthesizer of radium. It also was graced by the presence of many of the pioneer radiologists and scientists who had started radiology. From France, Antoine Beclere B from Britain, Thurston Holland B from the USA, Francis Williams, George Pfahler, Henry Pancoast and many of the great contemporary physicists.

The fourth congress in 1934 in Zurich settled into the pattern of scientific papers during the day, followed by banquets in the evening and tours for the ladies. Conference centers were away in the future. The meetings were held in hotel ballrooms and the dinners were held in the fanciest castles and public places in the host city.

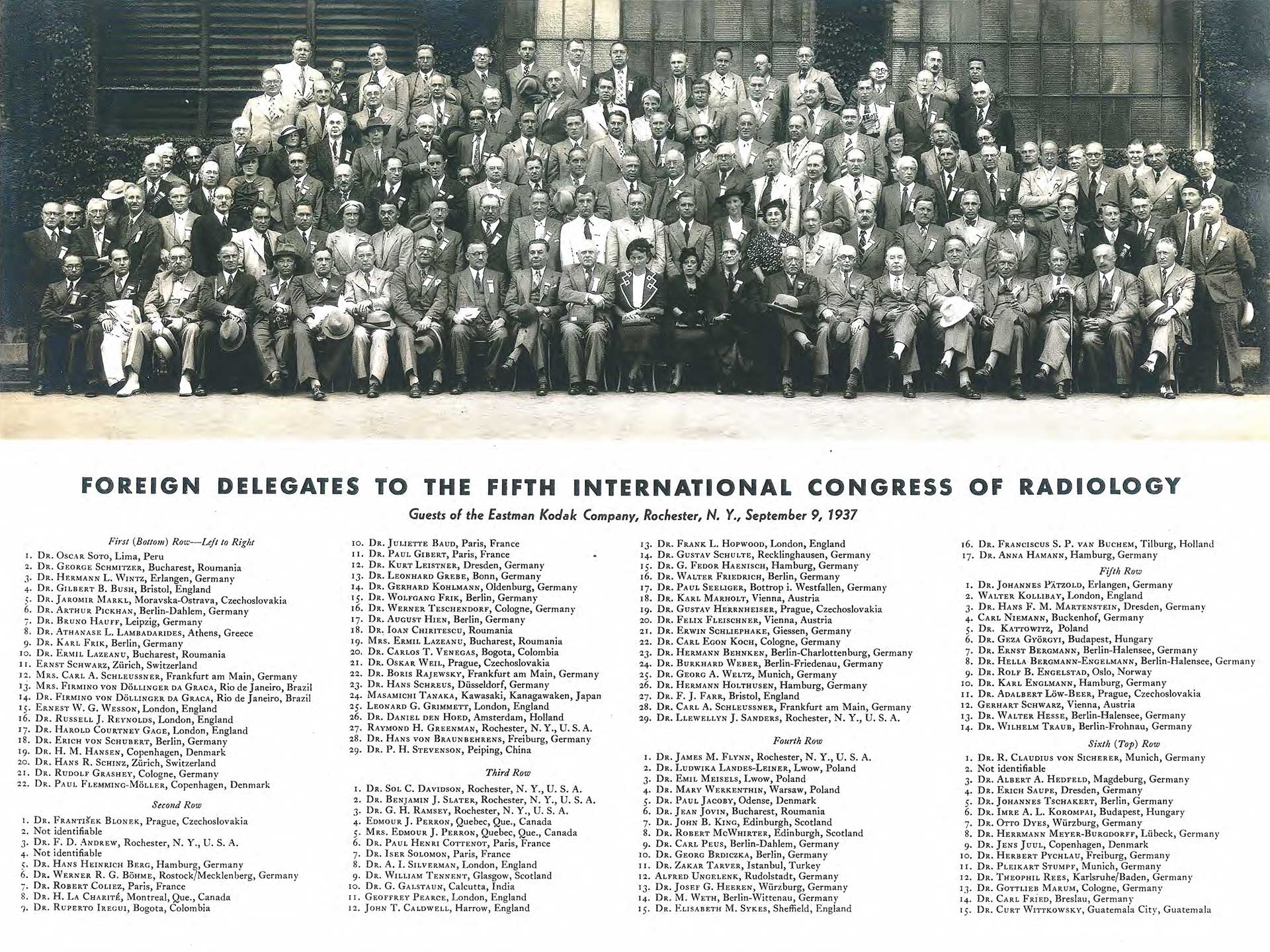

The fifth congress in 1937 was held in Chicago, well away from the grand circuit in Europe. The American societies combined to sponsor it. Benjamin Orndoff, who had helped organize many of those societies, was the secretary-general. Some of his files, those not sent forward to Germany, are the earliest surviving records of the ISR. They are now housed in the archives of the American College of Radiology. Under the organization of Otto Glaser, a distinguished physicist and Roentgen’s biographer, the congress produced a book entitled, “Science of Radiology,” in which leaders of the discipline summarized the state of practice in radiology. As well, the congress produced programs in several languages, a book of members in several languages and souvenirs of a visit to Chicago.

After World War II, the congresses resumed where they began, in London in 1950. By now, a very few delegates braved international air travel which was beginning to replace more leisurely trains and ships. The program featured presentations of advances drawn from scientific discoveries born in wartime needs. Much was said about new megavoltage sources of x-rays and other radiation forms for cancer treatment. The cornucopia of artificial isotopes from cyclotrons and reactors promised new dimensions in organ imaging and targeted radiation treatment. After a wartime hiatus, the international commissions resumed their activities agreeing to meet in 1953.

By 1953, when the congress met in Copenhagen, there was general agreement that the ad hoc arrangement by which national sponsors passed along the burden of meetings was not satisfactory. With the leadership of Flemming Norgaard, the International Society of Radiology came into being. Bylaws were drawn up, working committees in education and meeting planning were organized, national society dues were set. Dr. Norgaard agreed to serve as the society’s first secretary-general. The radiologist from the sponsoring society who had been president of a congress was, by that token, president of the ISR until the next meeting. A small executive committee was created. The president of the organizing group for the next congress was then president-elect of the international society and would become president when his congress occurred.

The 1956 congress returned to the Americas, to Mexico City, where radiologists from Latin American made up a larger share of registrants than ever before. Then, in 1959, only 18 years after the original intent to go to Germany, radiologists gathered in Munich for the ninth congress. Papers included much more progress in the use of isotopes, and a new and exciting development image intensified fluoroscopy. Other papers described the wonders of angiography with direct vascular sticks and from Sweden the use of catheters to place contrast anywhere in the vascular system. A new megavoltage therapy device, the linear accelerator, and cobalt 60 generators marked progress in radiation treatment for cancers.

The tenth congress in 1962 in Montral was my first one. I was loaned to the Canadian Association of Radiologists to help with a public relations effort. The sophisticated effort included a team of interpreters from the United Nations to provide simultaneous translation in five languages. It was an elegant and costly operation. The president and secretary-general took second mortgages on their

homes to raise working capital and were bailed out after the congress by donations from their colleagues in the CAR.

The 1965 congress in Rome attracted several thousand delegates for a solid program in both diagnosis and radiotherapy, with participation by physicists and by radiographers. A solid commercial exhibit section accompanied scientific posters and helped meet expenses.

In 1969, more than 3,000 delegates went to Tokyo in September for the first congress in Asia. A major typhoon passed through the area just days before the congress began. The industrial renaissance of Japan was just beginning and the bulk of papers still came from Europe and North America.

The three-year interval was made four years, with the next congress in 1973 in Madrid, Spain. Nearly 5,000 delegates registered for a solid program. Then came the 1977 congress in Rio de Janiero, Brazil. This first meeting in South America was beset by logistical problems. Meeting sessions were held in a new not-quite complete convention hall, some miles away from hotels. Bus service was irregular.

In 1981, the congress returned to Europe and to Brussels. Registration was strong and the program reflected a gradual evolution from the presentation of new work by speakers to review papers and teaching sessions.

The 1985 congress was sponsored by the United States and held mid-summer in Hawaii. Part of the basis of the site was to make it more available to radiologists from Pacific rim countries. The program continued the shift to teaching sessions. Because Hawaii was expensive and quite a distance from most centers of radiology, attendance was only about 1,500.

Four years later, the congress in Paris used not one but two major convention centers and delegates traveled via the Paris Metro. For the last time, the program featured both diagnosis and therapy. Subsequently, reflecting the division of the two tracks within radiology, a new international body for radiotherapy was created, leaving the ISR with the broad field of diagnosis. Reported attendance was some 7,000 persons, the highest of any congress.

After a decade from 1953, Flemming Norgaard had passed the secretary-general’s mantle along to Eric Samuels of Scotland and later South Africa. After his own decade, Dr. Samuels was succeeded by Walther Fuchs, a Swiss radiologist. For another decade, Dr. Fuchs embodied the society, carrying the full burden of management and finances.

By late in the 1980s, a renewed executive committee began taking a more vigorous role. They recognized the danger of vesting the society’s affairs entirely in one individual. The position of treasurer was created. Joseph Marasco of the US was the first treasurer. He enlisted the help of the financial managers of the American College of Radiology to handle the investments and daily money management for the society.

The next congress slid into early 1994 in Singapore under the management of a dynamic radiologist, Lenny Tan. Dr. Tan headed an effort to restructure the society, adding a slate of officers and placing top management in the hands of an elected president. Carl-Gustaf Standertskjold-Nordenstam had succeeded Dr. Fuchs as secretary-general. In 1995, it was decided to support the secretary-general with professional association management. The American College of Radiology agreed to provide that service, with your speaker as the newly-designated executive director.

At this point, the society had a continuing presence and structure independent of the ad hoc structures created for each congress. The society’s finances were enhanced when it took over custody of the Antoine Beclere fund, with revenues from the capital to be used for education. Dr. Tan also contributed a significant amount from the surplus on his Singapore congress. This gave the society a financial base in dues from national societies plus the interest on about a million dollars in capital. The society was not rich. But it was solvent.

At Singapore a decision was made to hold congresses on a biennial basis and to make them entirely teaching exercises. A second decision was made to seek congress venues in parts of the world not already served by multiple conventions. By that token, no congress would again meet in Chicago, where the Radiological Society of North America is in permanent residence. Nor would it go to Vienna, where the European congress settled.

The 1996 congress was in Beijing, China, the first in that country. The program featured radiology-pathology correlation with the core faculty drawn from the radiology registry of the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. More than 5,000 radiologists registered, with every session full.

In 1998, the congress venue was New Delhi, India. The congress organizers overcame massive logistical problems to present a solid teaching program for another 5,000 registrants. A bus service between the meeting center and hotels was impeded by several days of late monsoon rains. The teaching program emphasized ultrasound, which is widely used in Asia, over CT and MRI which are scarcer.

After three congresses in Asia, the 2000 meeting was organized by the Argentine radiology societies in Buenos Aires. Again, registration was some 4,500, and a solid program with special sessions for radiographers drew packed session rooms.

The ISR had hoped to place a congress in the middle east. But political unrest in that part of the world prompted a change. On short notice, the Mexican Federation of Radiology and Imaging undertook the 2002 congress in the resort of Cancun. The program was solid, but attendance was less than the previous several congresses.

After the 2004 congress, the first session in Africa will take place in year 2006 in Capetown, Republic of South Africa. This will be followed by a congress in year 2008 in Marrakesh, Morocco.

In the past decade, the ISR has sought to broaden its efforts beyond congress sponsorship. The International Commission on Radiologic Education has been revived under Holger Pettersson. The society has emphasized its liaison efforts with the World Health Organization, International Atomic Energy Agency, International Labor Office, Pan-American Health Organization and other international scientific bodies. In recognition of their impact on world radiology, permanent seats on the ISR executive committee were assigned to the European Association of Radiology, Asian Oceanian Society of Radiology, Inter-American College of Radiology and the American College of Radiology. The society has stimulated organization of regional societies in Africa and the middle east in the face of great difficulties in both areas.

Thus, over most of a century, the ISR has grown and mutated to meet the needs of its constituents. Some 86 national societies are now on the rolls. Its liaison programs are growing. It has opened several cooperative education efforts with leading manufacturers. At a recent strategic session of the executive committee, it was agreed that if there were no international society, someone would have to start one. That should not be necessary.